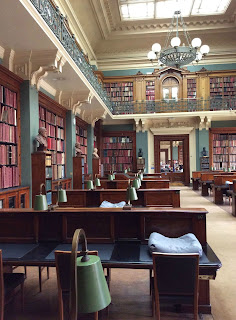

Places: St. Paul’s Cathedral Library and the National Art Library

Times: 10 a.m. - 11:30 a.m. and 1:30 - 3:00 p.m.

Temperature: 23° C

Song of day: Dear hearts and gentle people by Bing Crosby

Visiting a rare book or special collections library, at institutions such as St. Paul's Cathedral and the National Art Library, is like walking into a treasure trove of primary sources filled with beautiful old books and manuscripts. These visits remind me that such materials are important resources for researchers but helping students gain "primary source literacy" is a challenge for those of us doing information literacy instruction, especially if we only have "one shot" to teach a range of literacies (Daines & Nimer, p. 1). Should we try to include such sources and, if so, what and how to teach?

|

| On the steps of St. Paul's ... like the little old bird woman. |

"How to readers take books out of the library?" This seems like an innocuous question but after an hour with Joseph Wisdom, I have a feeling that a teachable moment is upon us. Joseph Wisdom is the librarian for St. Paul's Cathedral and responsible for a collection of ecclesiastical tracts, pamphlets, manuscripts and books that date back to the early 1700s and are consulted by scholars from around the world. During our one-hour tour, I realize that he is trying to share not just information about the history of the library but also something of his philosophy of librarianship ("we should do what we do with love").

Instead of simply answering my shelf question by describing the borrowing policies, Mr. Wisdom takes the opportunity to demonstrate how to handle rare books. Even though we are at the end of the session, he is still willing to take the extra few minutes to teach us this skill, which is critical to primary source literacy.

"Press in on the volumes on either side of the book you want, grasp your book gently, support it underneath and at 110 degrees from [the shelf] and pull it out. Read it flat so that there is no damage]."

Although the rest of the information about the library and the collection is interesting, it is this moment I will remember--for the skill itself and because Mr. Wisdom took the time to teach, even though he only had "one shot" and thus not a lot of time to do so.

|

|

|

All of these "logistics" are critical to using such sources for research and important for beginners like me to understand if we are to develop a literacy related to such materials. As Daines and Nimer (2015) point out, traditionally the use of such sources has been seen as the limited territory of areas of historical research--art history, political history, social history--and information literacy skills for using such primary sources has been limited to specialized fields. For example, a recent case study at McGill University was a collaboration between a rare books librarian and an art history professor (Garland, 2014).

However, Daine and Nimer (2015) seem suggest that students in other areas could benefit from being introduced to the use of such sources and I am rethinking their use for my subjects. Certainly students in Indigenous Studies, grappling with current issues such as that of the residential schools, might benefit from some preliminary instruction--not just in how to access and handle rare books but also perhaps some of the information seeking behaviour of historians, as described by Duff and Johnson (2002), might be transferable to other disciplines. Even highlighting one source (or using my experiences from this summer) might be worth developing into a session for students.

This would be a challenge--given the tendency of some professors to only allot one-hour "one shots" for information literacy instruction. But it's worth a shot.

References

Danier, G. D. and Nimes, C. L. (2015). In search of primary source literacy: Opportunities

and challenges. RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage

16(1), 19-34.

Duff, W. M., & Johnson, C. A. (2002). Accidentally found on purpose: Information-seeking

behavior of historians in archives. Library Quarterly, 72(4), 472.

Garland, J. (2014). Locating Traces of Hidden Visual Culture in Rare Books and Special

Collections: A Case Study in Visual Literacy. Art Documentation: Bulletin Of The Art

Libraries Society Of North America, 33(2), 313-326.

Bonus video!

No comments:

Post a Comment